A rosebush, planted in 1763 to commemorate a wedding, still grows in the garden. Nearby, a giant chestnut tree, planted in 1776 in honor of the Declaration of Independence, casts shade over the historic Georgian mansion. A spring, once used to fill casks on tall ships, still runs in the stone basement. Even greater treasures, from the earliest days of the nation, await indoors. The Moffatt Ladd House provides a stunning glimpse into nearly every facet of life in early American history. Step inside, and discover the people, free and enslaved, who shaped a community and influenced a nation.

A display of wealth and power

The remarkable home, which took at least eleven men three years to build, was a gift from wealthy English merchant, John Moffatt, to his only son, Samuel. It was a lavish wedding present, intended to present Samuel as a worthy businessman, and to display his father’s success. It was meant to impress, and it still does, as I discovered on my recent tour.

The main entrance to the home brings visitors into the Great Hall. Here, the large, open space is graced with a staircase, paneling and many hand-carved details, like modillions and rosettes. My guide pointed out that the huge soffit below the staircase came from a single tree. A tree of this size would normally have been reserved for the King, whose navy required large trees for masts. Its use here demonstrated John Moffatt’s wealth, power and connections.

The Great Hall is an enormous and impressive room. The 1820 Parisian wallpaper remains intact.

From the Great Hall, the tour progresses to an ornate parlor. Here, we meet four members of the Moffatt family: John; his wife, Katharine; their daughter, also Katharine; and Samuel. Their portraits, original to the home and beautifully restored, gaze over the London-made Chippendale furniture and velvet-flecked wallpaper.

Upstairs, a large bedroom called the Yellow Chamber features beautiful yellow bed curtains and 17-century furniture. My guide stated that other than a family’s silver, bed curtains would have been their most valuable household possession. The bed here is surrounded by beautiful yellow curtains. The room also features yellow and brown wallpaper with panels that depict English hunting scenes.

A room known as the Green Chamber probably served as a bedroom for the house’s most famous occupant, William Whipple, who married Katharine Moffatt (his cousin). The furniture is covered with a green check pattern favored by the Whipples. There is also a posthumous portrait of William, who fought in the Revolution, signed the Declaration of Independence, and planted the massive chestnut tree next to the home.

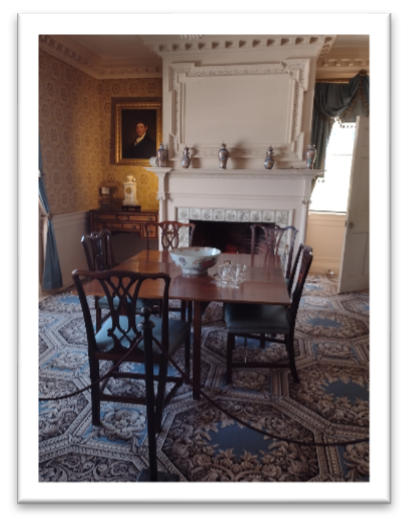

The dining room reflects 19-century improvements

The 18-century kitchen

Humbler spaces

The tour concluded with a visit to the third floor, which includes a nursery and several small bedrooms for servants. The enslaved people in the home probably also slept on this floor, and possibly in the large attic above. It is a simple and spartan space, compared with the luxury on display throughout the rest of the building. Samuel Moffatt’s daughter, Polly, scratched a short poem (still visible) into one of the nursery’s windowpanes. The third floor also features an enlarged version of an important document, the 1779 freedom petition. It was signed by Whipple’s slave, Prince, and other enslaved men in Portsmouth. Using the rhetoric that the enslaved men heard from their owners, the document declared that slavery was incompatible with the ideals of the Revolution. The New Hampshire legislature chose not to act on the petition, and it was published in a local newspaper as an “amusement” for readers.

Great power, great privilege, and often, great tragedy

His portrait still hangs in the parlor, but the sight of the home would be a bittersweet one for Samuel Moffatt. He and his wife, Sarah Catherine, enjoyed a few good years here, but Samuel’s poor record-keeping and lack of business sense led to ruin. Fearing debtors’ prison, he fled in the middle of the night to the Caribbean, and never returned. His wife eventually followed him there, and they attempted to establish a cotton plantation. Samuel died of fever, and Sarah Catherine later returned to Portsmouth.

In spite of John Moffatt’s great hopes for his son, it was daughter Katharine who kept the family afloat. She cared for two of Samuel’s children left behind when Sarah Catherine joined him in the Caribbean. She also cared for her father, who moved into the house when her mother died. Katharine’s marriage to William Whipple brought her the respect and esteem of the community, but William died when he was 54, and the couple had no children. (Katharine had two miscarriages, and their only son died at age one.) Her father agreed to leave Katharine a farm and an assurance that she could live in the house after his death for 16 years. However, Moffatt left the house to Samuel’s oldest surviving son. This led to a long legal battle within the family.

Despite the legal squabbling, the house remained in the family for 150 years. Its last permanent resident, A.H. Ladd, was a colorful man who loved gardening, chased would-be thieves out of the home, and killed a whale in the Portsmouth harbor. He made several improvements to the home and garden before his death in 1900.

Ladd’s descendants turned the house over to The National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in the State of New Hampshire. The Society still operates the home as a museum. Its preservation efforts include restoring the mansion one room at a time. The current effort focuses on the Yellow Chamber, where a plan to install a more accurate reproduction of the wallpaper will soon be underway. The organization welcomes donations to support this project.

The Moffatt-Ladd House, at 154 Market Street in Portsmouth, is open every day except Wednesdays, from June 1st to October 15th, from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tours begin every 45 minutes, with the last one starting at 3:30 p.m. The home will part of the Portsmouth Historic Sites Association’s Twilight Tour on August 11. Tickets for this event, which includes visits to eight historic sites, can be purchased at Events | portsmouthistoric (portsmouthhistoric.org)

For more information about the Moffatt-Ladd House, please see Visit – Moffatt-Ladd House & Garden (moffattladd.org) or call (603) 436-8221.