Nearly 40,000 acres have burned in the recent California wildfires. That’s almost four times the size of Portsmouth.

Portsmouth has its own history of destructive blazes, dating back to the community’s earliest years.

Throughout the colonial era, night watches patrolled the community, searching for fires.

Watchmen would cry out the location, and church bells would ring to alert citizens, who were required by law to participate in quelling the conflagration. Some of our historic homes still have fire buckets from this era, many painted with the names or initials of their original owners.

At a special town meeting held in 1756, voters agreed to purchase fire tools and buckets, and elected 12 “firewards” to oversee fire protection. In 1774, a committee was established to buy a “New Ingine.”

Boston had a firefighting engine as early as the 1650s. These early machines bore little resemblance to today’s fire trucks.

Portsmouth’s 1774 “Ingine” was a pump on wheels with long handles. Whether it was used or not in the City’s first major fire, in 1781, that disaster burned the jail and the homes of Governor John Langdon and others.

Many residents joined “fire societies,” which existed not so much to fight fires as to protect property recovered from a fire. Members carried special keys to take apart bedframes – highly valued pieces of furniture at the time.

Three large fires in the early 1800s changed Portsmouth dramatically. The first occurred in 1802.

The New Hampshire Gazette reported that the fire began at the New Hampshire Bank building early on a Sunday morning, and by the time it had been discovered, “the whole town was threatened with immediate destruction.”

Portsmouth residents stopped the fire by pulling down buildings in advance of the flames and engaging everyone in the battle, including women who had just lost their own homes. The Gazette recalled:

Let it be recorded to the honor of a great number of females, that after being burned out of house and home, instead of fleeing from the fire in despair, they immediately joined themselves to the company and lanes of the hardier sex, and stood and handed water, until they were on the point of fainting! – dying!

The author lamented, “The whole beauty of the town is gone! – is gone!!!”

In 1806, the Gazette reported on another massive fire, noting that the buildings burned “were all wooden…only one brick partition wall, completely saved a row of buildings (sic). This, we think, should most thoroughly convince the people…of the utility and importance of building with brick.”

When 1813 brought yet another disastrous fire to Portsmouth, the citizens decided they had had enough. They voted to prohibit wooden structures over 12 feet tall, leading to the construction of the brick buildings that comprise Portsmouth today.

The community enhanced its firefighting measures over the years, as Steven E. Achilles noted in “Images of America: Portsmouth Firefighting.”

New lessons came with each improvement. When firefighters received their first suction engine, “Washington No. 2,” they left it behind when fires broke out.

“The men not knowing what the suction was for, it lay about the house useless, and at fires they filled the engine from water buckets,” former Mayor and fireman Col. William H. Sise recalled. “One day, someone accidentally found out what the suction was intended to do and thereafter the firemen devoted to its proper care.”

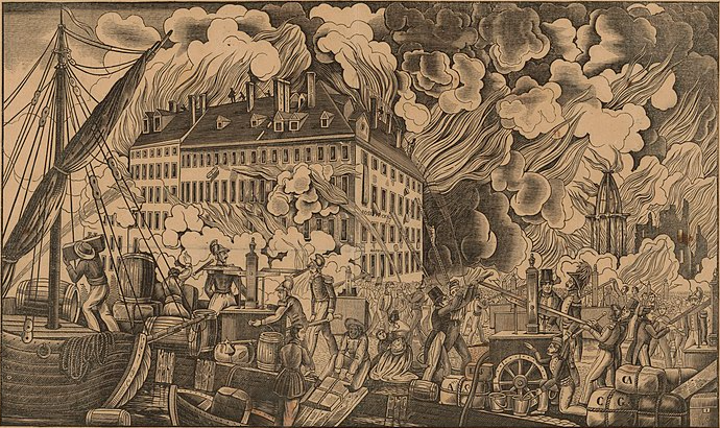

Fires have plagued most major cities. Here, a crew uses a pump to fight a fire in New York. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Additional fire stations were built, trucks replaced horse-drawn wagons, and ladders ascended to ever-greater heights. The department purchased an 85-foot aerial ladder truck in 1941, Achilles wrote, and the fully extended ladder reached 9 feet above the clock on the North Church steeple.

As with the decision to build with brick instead of wood, each fire presumably taught new lessons to the people of Portsmouth.

Los Angeles will have to reckon with the causes of its fires, and the problems that made the catastrophe worse, such as the lack of water pressure in hydrants and the slashing of $17 million in funding to the fire department.

Although it seems tangential to ask it here, one wonders whether Angelenos were aware of these problems before the fires. Were they reported in the newspaper, or on local news websites?

It is a reminder that local news does matter. Citizens ought to ask themselves regularly if they are getting the whole story from their preferred media outlets.